See, the problem with historical novels, particularly the ones about visionaries and rebels, is that even if you know little about the period or person, you can pretty much count on them ending badly. The author can also be a clue about the relative happiness of the ending and when you read Sharon Kay Penman, whose first novel was a sympathetic account of the life of Richard III, you can bet that she picked a heroic but ultimately tragic figure for follow.

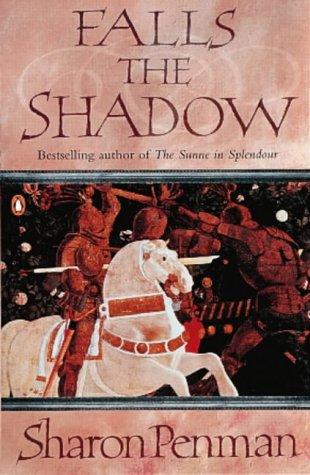

Falls the Shadow is a tragedy, even the name gives it away. It follows the life of Simon de Montfort and Llewelyn of Wales. This isn't Llewelyn Fwar (the Great) who was one of the main characters of Here Be Dragons, rather, it's his grandson, who is trying to hold together his grandfather's dream of a free or at least a united Wales against the treachery of his brothers.

But for all this trilogy is ostensibly about Wales, the main character of this book is Simon de Montfort. He's one of those men who crops up in history from time to time, someone who is just plain ahead of his time in many ways. Penman shows us a man who truly believed that his God-given duty as a knight was to look after people more helpless than himself. In the course of his life, he managed to force the King of England--Henry III, son of King John and not much better a ruler than his father--to not only honor the Magna Carta but also the Provisions of Oxford, a much more democratic outline for governing.

Deposing a king was srs bizns back in those days and Simon claimed he did everything in the King's name, that his quarrel wasn't with Henry, who was his brother-in-law--Simon married Eleanor, Henry's sister--but with Henry's useless advisors. During Simon's period of control, the first elected parliament met in England. Granted, the only people who could vote were those men who held property worth 40 shillings or more, but still, we're talking about the middle of the 13th century here.

And in the end, of course, that was the problem. Instead of giving more power to the barons and other nobles, Simon's Provisions favored the very small, nascent middle-class--the Provisions of Oxford was the first legal document published in English since the Conquest. It was just too early for this kind of thing, plus, in the end, Simon faced a much more serious opponent than the dithering Henry: Henry's warrior son, Edward, later known as Edward I or Edward Longshanks.

And Wales? It gets very short shrift in this book, but at the end of the book, Llewelyn is still free and trying to hang onto his country. Even without reading it, I know that the next book in the series--The Reckoning--will see the end of his fight and not in a good way. After all, these days the Prince of Wales is an Englishman, not a Welshman.

So why read something when you're pretty sure going in that it'll all end in tears? To know how it happened, and to see one version of what the people involved might have been thinking. After all, look at how many versions of the Arthurian legends have been written and how popular Colleen McCullough's Masters of Rome series is. Without Simon de Montfort and the Provisions of Oxford, which didn't last long after his death, the history of English democracy and eventually US democracy might have been very different. Which would be why, even though very few people have heard of him, there's a plaster relief of his head in the chamber of the United States House of Representatives. I get the feeling that de Montfort, or at least Penman's version of him, would be honored.

No comments:

Post a Comment